Vellum-Aura: The Calligrapher’s Erased Word

The moment the heavy, leather-padded door to Vellum-Aura closed, the air was immediately cold, dry, and held the distinct, sharp, chemical odor of dried ink and old, fine paper. The name, combining the material of writing with an ethereal glow, perfectly captured the manor’s strange, scholarly atmosphere. This abandoned Victorian house was structured not for lively conversation, but for silent, meticulous production, its large, north-facing windows designed to provide the unwavering light essential for its resident’s painstaking craft. The silence here was the deep, focused quiet of a monk’s cell, a pervasive stillness that seemed to demand reverence for the written word.

The final inhabitant was Mr. Alistair Rourke, a brilliant, but intensely reclusive master calligrapher and illuminator of the late 19th century. Rourke’s profession was the creation of exquisite, highly complex manuscripts and illuminated texts for private collectors. His singular obsession, however, was not beauty, but absolute textual permanence—the creation of a single, perfect, unalterable word that could not be erased, edited, or misinterpreted. After a catastrophic fire destroyed his life’s work (a magnificent illuminated Bible), he retreated to the manor. He dedicated his final years to writing the ‘Final Edict,’ a single sentence containing the ultimate, unyielding truth of existence, written in a flawless script. His personality was intensely rigorous, fearful of error and revision, and utterly consumed by the pursuit of immutable perfection in every line, stroke, and flourish.

The Pigment Laboratory

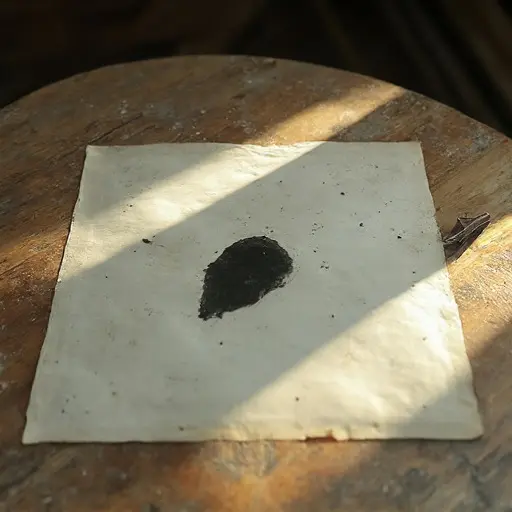

Rourke’s mania culminated in the Pigment Laboratory. His journals, written in a tiny, almost microscopic script and found inserted into the lining of a false-bottomed inkwell, detailed his descent. He stopped using conventional inks, developing his own indelible formulae that chemically bonded to the vellum. His final project was the ‘Ultima Nigredo’—an ink so profoundly black and permanent it could not be removed by any acid or mechanical means. “The word must be as final as fate,” he wrote. “The ink must be extracted from the pure, unadulterated essence of the final, unyielding darkness.”

The house preserves his fastidiousness. Many interior walls are covered with long, perfectly drawn, parallel pencil lines, used by Rourke as visual guides for the proper spacing and alignment of his unseen, imagined text.

The Final Stroke in the Abandoned Victorian House

Mr. Alistair Rourke was last seen working at his desk, preparing his vellum, the strong scent of his chemical ink filling the room. He did not leave the manor. The next morning, the scriptorium was silent and cold. No body was found, and the vast quantities of vellum he ordered remained stacked in their boxes.

The ultimate chilling clue is the blank sheet of vellum. It holds no text, no Edict, only the single, final, flawless ink blot of his Ultima Nigredo. The obsidian stylus, meant to erase, was never used. This abandoned Victorian house, with its silent walls and scholarly gloom, stands as a cold, imposing testament to the master calligrapher who pursued the perfect, permanent word, only to realize that the most profound and unalterable statement was the one he ultimately chose not to write.