The Final Stain of Rubric-Erosion Keep

Rubric-Erosion Keep was an architectural statement of ethical rigor: a massive, symmetrical structure built of pale, smooth granite, characterized by numerous internal chambers designed to eliminate passion and subjective influence for concentrated moral reasoning. Its name suggested a blend of established rules/codes (Rubric) and the gradual destruction/wearing away (Erosion). The house stood on a remote, high, isolated mesa, giving it an atmosphere of complete intellectual detachment, perpetually dedicated to the singular pursuit of moral truth. Upon entering the main jurisprudence studio, the air was immediately thick, cool, and carried a potent, mineral scent of aged paper, dried ink, and a sharp, metallic tang of brass. The floors were covered in heavy, smooth tiles, now slick with dust and grinding residue, amplifying every faint sound into an unsettling echo. The silence here was not merely quiet; it was an intense, ethical stillness, the profound hush that enforces the memory of a moral principle perfectly stated, waiting for the final, unassailable absolute. This abandoned Victorian house was a giant, sealed law book, designed to achieve and hold a state of absolute, unchangeable, fixed moral certainty.

The Ethicist’s Perfect Law

Rubric-Erosion Keep was the fortified residence and elaborate workshop of Master Ethicist Dr. Elias Thorne, a brilliant but pathologically obsessive moral theorist and logician of the late 19th century. His professional life demanded the relentless categorization of human action, the flawless construction of universal ethical laws, and the pursuit of absolute moral consistency—a principle so pure that it admitted zero exception, contradiction, or situational context. Personally, Dr. Thorne was tormented by a crippling fear of moral relativism and a profound desire to make the chaotic, mutable nature of human behavior conform to a state of pure, silent, permanent categorical imperative. He saw the Keep as his ultimate constitution: a space where he could finally design and engrave a single, perfect, final, unyielding law that would visually encode the meaning of eternal, fixed morality.

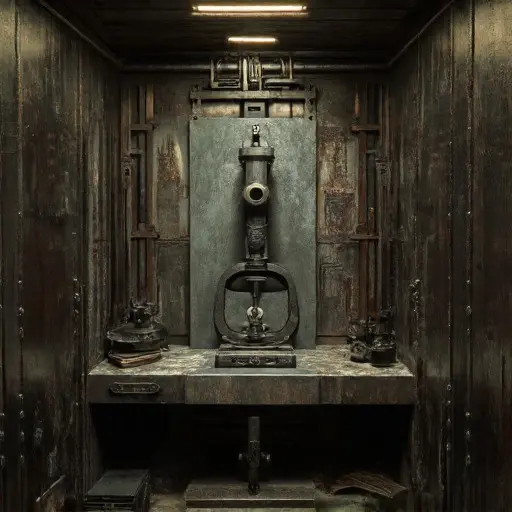

The Absolute Vault

Dr. Thorne’s Absolute Vault was the engine of his obsession. Here, he worked to isolate and stabilize his final, most critical law. We found his final, detailed Moral Compendium, bound in thick, heavily varnished steel covers. His entries chronicled his escalating desperation to find the “Zero-Exception Principle”—a moral law so perfect it applied equally and identically to all beings in all situations. His notes revealed that he had begun to believe the most chaotic element was the concept of consequence itself, which introduced uncertainty and utility into pure duty. His final project, detailed meticulously, was the creation of a massive, unique, internal “Master Law”—a final, massive sheet of pure copper upon which he would mechanically emboss his ultimate, single, perfect, unadorned, moral absolute: a simple command to Act.

The Final Law

The most chilling discovery was made back in the main studio. Tucked carefully onto the center of the judgment bench was the Master Law. It was a massive, smooth, rectangular sheet of polished copper, affixed firmly to the desk. The copper was engraved with a single, massive, perfectly formed circle—a single, unassailable, simple geometric shape etched deep into the center of the plane. The mark was utterly flawless, representing the absolute perfection of the command to Act (to complete the loop, to begin and end in the same place, a closed system of duty), but without defining what to act upon or why. Resting beside the copper was a single, small, tarnished engraving stylus, its tip broken and coated in a fine, metallic residue. Tucked beneath the desk was Dr. Thorne’s final note. It revealed the tragic climax: he had successfully engraved his “Master Law,” achieving the absolute, unadorned, eternal principle of duty he craved. However, upon completing the final, simple circle, he realized that a principle so perfectly free of any defined object or context was a law that was utterly unactionable—a perfect command that was fundamentally meaningless. His final note read: “The law is fixed. The consistency is absolute. But the truth of a principle is in the lives it guides.” His body was never found. The final stain of Rubric-Erosion Keep is the enduring, cold, and massive engraved circle on the polished copper, a terrifying testament to an ethicist who achieved moral perfection only to find the ultimate, necessary flaw was the removal of the very context and consequence that gives meaning and utility to a moral code, forever preserved within the static, intellectual silence of the abandoned Victorian house.}