The Eerie Stillness of the Myrtal-Haven

The Myrtal-Haven, a rambling, asymmetrical Neo-Jacobean mansion built in 1895, is defined by its dark red brick, extensive use of classical pilasters, and its long, prominent glass Conservatory. It sits low in a hollow, perpetually damp and shaded. To step across its decaying threshold is to encounter an immediate, penetrating coldness and a silence so deep it feels like pressure on the eardrums.

The Conservatory, once a beacon of vibrant life, is now a scene of spectacular, eerie decay, a clear statement that the house’s abandonment was not gradual, but absolute and final. Every rusted iron beam and every dead fern leaf holds the history of an internal collapse.

The Anxious Horticulturalist, Arthur Leland

The mansion was built by Arthur Leland (1855–1910), a man whose profession was rooted in the methodical, patient science of botany and experimental horticulture. He was not a traditional industrialist but an obsessive scientist, using his inherited fortune to pursue his research. Socially, he was painfully awkward, preferring the company of his rare plants to human interaction.

Arthur married Clarissa Selwyn in 1880, a practical woman who sought a quiet, stable life. They had two daughters: Edith and Flora. Arthur’s personality was defined by chronic anxiety and a compulsive need for order, particularly in his experiments. His daily routine revolved entirely around the Conservatory and the adjacent Laboratory, where he worked to cultivate delicate, temperature-sensitive hybrids. His ambition was to breed a new, resilient species of orchid; his greatest fear was the fragility of his plants and the volatility of the outside world.

The Conservatory and Laboratory were his entire world, built as twin additions to the house, ensuring a perfectly controlled environment for his work.

The Exposure in the Laboratory

The tragedy that brought down the Leland family was a direct result of Arthur’s professional failure and his crippling anxiety. In 1909, after years of intense, isolated work, Arthur believed he had finally achieved his breakthrough: a new, deep-violet orchid hybrid. He planned a massive public unveiling—a rare venture outside his comfort zone—to secure funding for a research foundation.

However, a visiting scientist, reviewing Arthur’s data in the Laboratory, discovered a crucial, simple error in his temperature logging that invalidated the entire hybrid experiment. The orchid was not a new species; it was a known variant that had been manipulated by the faulty conditions. The failure was not a complex scientific one, but a basic, humiliating oversight caused by Arthur’s own isolation and stress.

The exposure triggered a total mental breakdown. Arthur, unable to face the public humiliation and the total invalidation of his life’s work, returned to the Laboratory. In a final, deliberate act of professional erasure, he methodically smashed every glass vial, every specimen jar, and every piece of scientific equipment in the room. He then walked into the Conservatory and quietly ingested a powerful poison he used for his most destructive pests.

The Abandoned Notebooks in the Nursery

Clarissa Leland, the widow, was left with a wrecked house, the stigma of her husband’s suicide and professional disgrace, and two young daughters, Edith and Flora. She was emotionally annihilated by the years of catering to Arthur’s extreme needs.

She refused to remain in the house for even a week. She immediately sold off only the household linens and tableware to raise enough money for travel and accommodation. She took her daughters and fled to her sister in a different state, leaving the Myrtal-Haven entirely full of Arthur’s useless, heavy scientific equipment and his destroyed, eerie collection of dead plants.

Clarissa’s final act was one of passive abandonment. She stopped paying the taxes immediately, ensuring the house would quickly become a problem for the authorities.

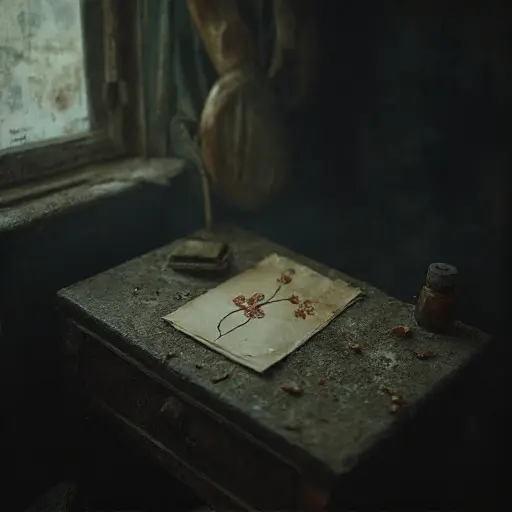

In the third-floor Nursery, where the two girls were raised, one object remains on the small, wooden desk: a stack of three school notebooks belonging to Edith. The notebooks are filled with her careful, childish sketches of her father’s beloved orchids and detailed, amateur taxonomic notes.

The Myrtal-Haven was seized by the state for tax delinquency but proved unsaleable due to the extensive damage in the Conservatory and the contaminated state of the Laboratory. It stands today, its glass roof cracked and its iron skeleton rusting, a vast, eerie monument to a fragile ego and the destructive power of a single, simple, scientific mistake. Its silence is absolute.