The Eerie Rituals of Cinder Ashlar

Cinder Ashlar is a house of stark contrasts: magnificent stone architecture rendered uniformly bleak by the constant residue of smoke. This abandoned Victorian house, built in a remote, desolate clearing, is characterized by its oversized chimneys and an unusual lack of interior wood—a structure deliberately fire-resistant. The atmosphere inside is overwhelmingly olfactory, smelling deeply of cooled embers, fine soot, and a metallic bitterness, like burned paper. The constant dust and the pervasive darkness create an eerie sense of deliberate concealment. The silence here is not empty, but heavy with the weight of things destroyed, giving the entire structure an air of profound, necessary secrecy and suspense.

Bartholomew Pyre: The Collector of Secrets

The owner of Cinder Ashlar was Bartholomew Pyre, a retired parliamentary scribe and archivist with a profound, almost pathological obsession with destroying—not preserving—information. Bartholomew believed that human happiness was dependent on the controlled, ritualistic elimination of evidence, records, and embarrassing personal histories. He built the house in 1890 as his private crematorium, specializing in taking delivery of sensitive documents and ensuring they were reduced to ash. He called his profession “The Cleansing.”

Bartholomew’s fate is a matter of profound melancholy and rumor. In 1915, the house was discovered locked and empty. On the main hearth, investigators found only a final, large pile of fine, white ash. The general consensus was that he had finally run out of other people’s secrets and had proceeded to destroy his own. The house, designed for destruction, now preserves the silence of total informational absence.

The Paper Vault’s Final Offering

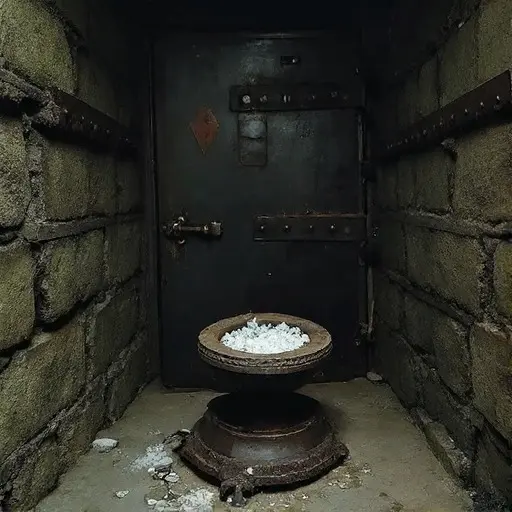

Hidden beneath the floor of the main study is “The Paper Vault,” a small, stone-lined chamber that served as Bartholomew’s staging area for destruction. This room is cold and still, the air heavy with the scent of old soot. The focus keyword, abandoned Victorian house, feels almost secondary to the vault’s sinister purpose.

In the center of the room sits a heavy iron brazier, now filled with a packed, uniform mass of fine, white ash. There are no identifiable scraps, no residual markings—total obliteration. Tucked into a crevice in the stone wall, a single, small, leather-bound book was overlooked. It is not a diary, but a ledger. The final page contains a list of dates and clients, with the very last entry written in faint pencil: “Self-Cleansing. No witnesses. 04.18.1915.”

The Master Bedroom’s Burnt Remnant

The master bedroom provides the final, personal insight into Bartholomew’s work. The room itself is damaged; near the main hearth, the wooden floorboards are deeply charred, suggesting a localized, intense fire was set. This was not accidental.

On the ornate marble mantlepiece, face-down, is a heavy, dark wooden picture frame. When carefully turned over, the glass is intact, but the picture behind it has been completely removed—leaving only a perfect square of clean backing board, untouched by the surrounding dust. Resting just inside the empty frame is the single remaining relic of Bartholomew Pyre: a small, tarnished silver signet ring, inscribed with the initials B. P.

Cinder Ashlar is not haunted by the presence of a ghost, but by the overwhelming, eerie absence of all history. The melancholy truth is that Bartholomew Pyre succeeded absolutely in his final goal, leaving his house as a monument to the perfect, silent destruction of identity and the enduring, cold silence of a clean slate.