Buried Secrets in the Shuttering of Wrenshaw House

The Kitchen Wing and the Cook’s Last Register

Wrenshaw House, a large villa, was once the property of a prominent family but was ultimately left in the care of its live-in staff following the family’s departure for the colonies in 1898. Our focus centered on the life of Mrs. Eleanor Crowe, the estate cook in service from 1885 until the house’s effective abandonment in 1902. Crowe, a widow with no children, remained on the payroll for several years, maintaining the property with minimal resources. Her fate remains opaque; she simply vanishes from the county registry after 1902.

The professional trace was most palpable in the vast, cold kitchen wing. The immense cast-iron range, manufactured by a long-defunct Birmingham firm, remained in the center, coated in a thick layer of coal soot and surface rust, yet its complicated system of flues and dampers was meticulously clean, suggesting maintenance until the very end.

Tucked into a small, dry space above the scullery sink—a space likely used to store dry goods—we discovered a small, thick, ledger book bound in sturdy canvas. It was not a recipe book, but a comprehensive, day-by-day Provision and Labor Register. It detailed every pound of coal, every dozen eggs, every hour of her cleaning labor from 1898 to early 1902.

The Locked Pantry and the Silent Resignation

The register itself provided the narrative arc. As the years progressed, the entries shifted. Initially, the ledger noted ingredients for large meals; by 1900, the entries were strictly for basic maintenance: lamp oil, cleaning powder, minimal coal. The final three pages, however, detailed the precise quantities of food purchased for a single person for a duration of six weeks, concluding on February 12, 1902, the very day the entries ceased.

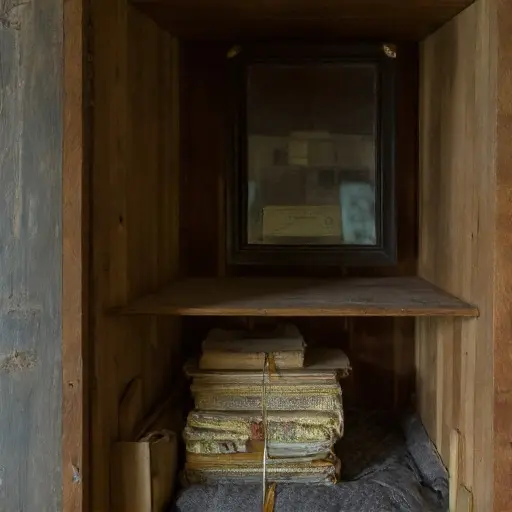

In the deepest corner of the scullery stood a small, locked pantry, designed to store valuable items. The key, found taped inside the spine of the ledger book, opened it to reveal not silver or wine, but a collection of Mrs. Crowe’s few personal belongings: a neatly folded, simple grey wool shawl, a small, framed photograph of her late husband in a railway uniform, and—most revealingly—a stack of sealed and stamped envelopes, all addressed to the estate’s overseas owners.