Silent Calder House and the Chair That Was Moved

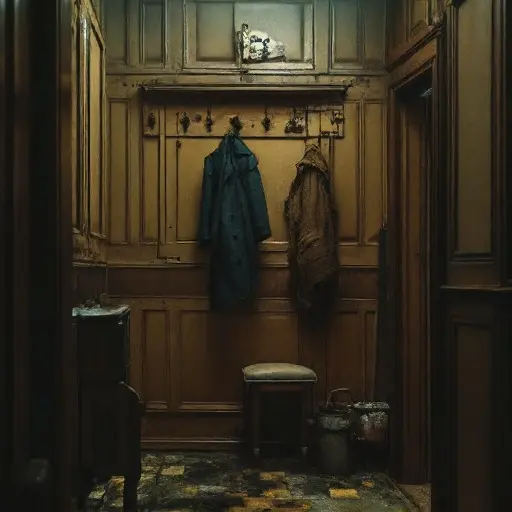

The hush inside Calder House begins with that sagging armchair, its indentation still shaped by long study. The air feels paused, grainy with plaster and old smoke, as if the walls themselves remember a moment that broke routine. No voices linger here—only the tension of a room left mid-breath.

Across the parlor floor, small scrapes mark a sudden movement, and one chair’s angle hints at a night when something was heard but never proven.

The Carpenter Who Remained Too Long

Alistair Rowan Calder, master carpenter-architect, born 1869 in Dundee, spent his evenings in this parlor refining private commissions once admired across the region. Middle-class pride edged his manner; his sister, Moira Calder, often teased that he measured days instead of living them. His tools show this: handles polished smooth, blades maintained with ascetic care. Here are his ambitions—miniature studies, mock joints, scaled stair spindles—each suggesting an exacting mind. A man of routine: tea at the mantel, sketches at dusk, soft humming as he tested balance by fingertip.

The Glint in the Wood

Sometime after a contentious commission for a wealthy investor, Calder’s precision soured into anxious revisions. A scorched patch at the parlor’s wainscot exposes wood shaved back, then re-stained—an alteration he never explained. On the mantel, a sealed envelope addressed only with initials bears a thumb-smudge of oil. Nearby, Moira’s brooch lies snapped, its pin embedded into a scrap of molding, as though used to pry loose a panel.

In the end, what remains is a hush around the moved armchair: Calder’s last place of rest, or confrontation. A faint indentation on the cushion’s edge suggests someone leaned close, perhaps Moira, perhaps another. Nothing explains the scorched wainscot or the missing contents of the open safe.

The house offers only its silence, and Calder House stands abandoned still.