Ethos-Erase: The Ethicist’s Final Principle

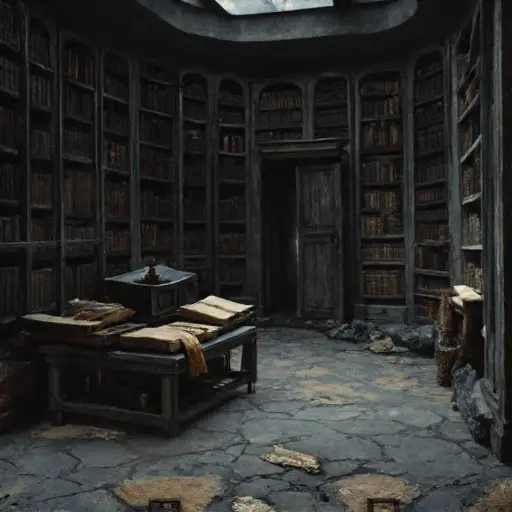

The moment the heavy, bronze-plated door to Ethos-Erase was pushed open, the air rushed out—cold, dense, and heavy with the pervasive, unsettling odor of dry parchment, stale leather, and the faint, coppery scent of spilled blood (perhaps from a minor injury). The name, combining a moral code with the concept of erasure or removal, perfectly captured the manor’s function: a physical space dedicated to finding the perfect ethical rule, now embodying its own absolute moral nullity. This abandoned Victorian house was structured not for domestic warmth, but for unwavering, logical asceticism, its internal layout a bewildering maze of small, unadorned cells and soundproofed chambers designed to eliminate all personal bias and emotional appeal.

The final inhabitant was Professor Gideon Pact, a brilliant, but intensely reclusive master ethicist and moral theorist of the late 19th century. Professor Pact’s profession was the study of human behavior, seeking to codify a universal, absolute set of moral principles. His singular obsession, however, was the creation of the ‘Zero Principle’—a single, perfect, flawless ethical rule that would, through the absolute synthesis of all previous moral philosophy, deliver the ultimate, objective truth of goodness, free of all cultural or personal interpretation. After a personal moral failure shattered his faith in the perfectibility of human conduct, he retreated to the manor. He dedicated his final years to resolving this single, terrifying goal, believing that the only way to achieve the Zero Principle was to understand the ultimate absence of all vice. His personality was intensely rigorous, fearful of subjective judgment, and utterly consumed by the pursuit of moral finality.

The Judgment Chamber

Professor Pact’s mania culminated in the Judgment Chamber. This secure, sealed room was where he spent his final days, not teaching ethics, but deconstructing the entire edifice of morality itself, attempting to define the ultimate ethical truth by isolating the perfect moral vacuum. His journals, written in a cramped, precise hand that eventually gave way to complex formulae involving logical paradoxes and moral algebra, were found pinned beneath the lectern. He stopped trying to define good and began trying to define the un-good, concluding that the only way to achieve the Zero Principle was to eliminate the need for any action whatsoever. “The rule is a fallacy; the consequence is a corruption,” one entry read. “The final principle requires the complete surrender of all choice. The truth must be a single, self-evident, unstated conclusion, contained in absolute inaction.”

The house preserves his ascetic nature. All internal doors are constructed with plain, unvarnished wood and no distinguishing hardware, forcing a uniform, unadorned experience throughout the manor.

The Final Principle in the Abandoned Victorian House

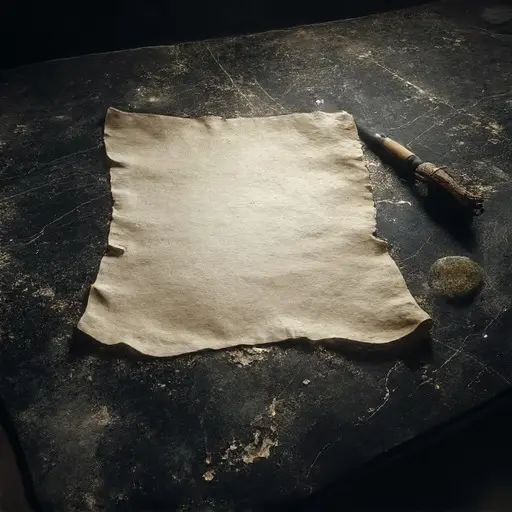

Professor Gideon Pact was last heard working in his study, followed by a sudden, intense sound of heavy paper being violently flattened and then immediate, profound silence. He did not leave the manor. The next morning, the study was cold, the shelves empty, and the man was gone. No body was found, and the only evidence was the singular, physical state of his final parchment.

The ultimate chilling clue is the blank parchment. It is the final declaration—the Zero Principle achieved, containing no rule, no judgment, and no human imperative. The smooth stone and clean quill knife ensure no further attempt could be made to write or enact a flawed law. This abandoned Victorian house, with its silent studies and empty shelves, stands as a cold, imposing testament to the master ethicist who pursued the ultimate, pure moral truth, and who, in the end, may have successfully composed the principle that demanded absolute inaction, vanishing into the unwritten, objective truth that he engineered as his final, terrifying statement of pure ethics.