Chroma-Fugue: The Painter’s Final Canvas

The moment the heavy, bronze-plated door to Chroma-Fugue was carefully pushed open, the air rushed out—cold, dense, and heavy with the pervasive, unsettling odor of volatile solvents, aged canvas, and the sharp scent of mineral white spirit. The name, combining color with a state of temporary memory loss or flight, perfectly captured the manor’s function: a physical space dedicated to capturing transient visual reality, now embodying its own loss of all vibrant sensation. This abandoned Victorian house was structured not for domestic warmth, but for unwavering, artistic control, its internal layout a bewildering maze of small, well-lit viewing galleries and dark, pressurized storage cells designed to preserve volatile paints and delicate canvases.

The final inhabitant was Mr. Quentin Shade, a brilliant, but intensely reclusive master painter and color theorist of the late 19th century. Mr. Shade’s profession was the creation of complex, emotionally resonant oil paintings, often focusing on the manipulation of light and shadow. His singular obsession, however, was the creation of the ‘Ultimate Hue’—a single, perfect, flawless color that would, through the absolute synthesis of all known pigments, reveal the ultimate, objective truth of visual perception, free of all subjective interpretation. After a catastrophic public showing where critics accused his final work of being ‘visually deafening,’ he retreated to the manor. He dedicated his final years to resolving this single, terrifying goal, believing that the only way to achieve the Ultimate Hue was to understand the ultimate absence of all color. His personality was intensely rigorous, fearful of visual impurity, and utterly consumed by the pursuit of chromatic finality.

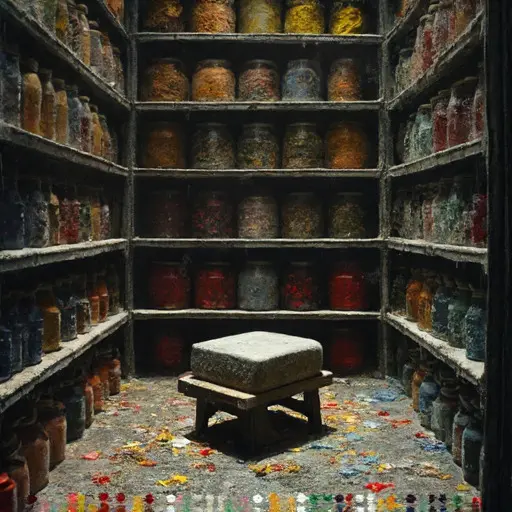

The Pigment Chamber

Mr. Shade’s mania culminated in the Pigment Chamber. This secure, sealed room was where he stored every color and tint he had ever considered and then deemed flawed or incomplete. His journals, written in a cramped, precise hand that eventually gave way to complex spectral analysis charts and theoretical color wheels, were found sealed inside a hollow block of dried clay. He stopped trying to paint color and began trying to synthesize the ultimate negative, concluding that the only way to achieve the Ultimate Hue was to eliminate the need for any reflective surface. “The color is a lie; the reflection is a trick,” one entry read. “The final hue requires the complete surrender of all light. The truth must be a single, self-evident, unstated conclusion, contained in an ultimate blackness.”

The house preserves his visual anxiety structurally. Many internal door frames and archways are painted with subtle, conflicting color gradients that shift under different lighting conditions, his attempts to create a universal test for visual perception within the manor.

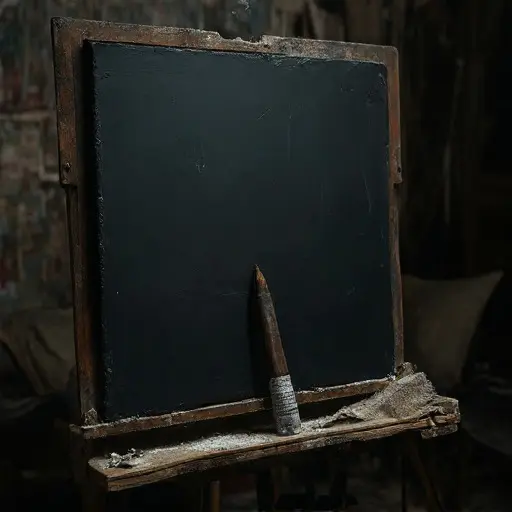

The Final Canvas in the Abandoned Victorian House

Mr. Quentin Shade was last heard working in his studio, followed by a sudden, intense sound of heavy wood breaking (perhaps from a collapsing easel) and then immediate, profound silence. He did not leave the manor. The next morning, the studio was cold, the pigment chamber sealed, and the man was gone. No body was found, and the only evidence was the singular, physical alteration to his final canvas.

The ultimate chilling clue is the black canvas. It is the final painting—the Ultimate Hue achieved, containing no light, no tint, and no form. The clean brush and dried white paint ensure no further attempt could be made to alter the pure state of blackness. This abandoned Victorian house, with its silent studios and sealed chambers, stands as a cold, imposing testament to the master painter who pursued the ultimate, pure color, and who, in the end, may have successfully composed the canvas that demanded absolute darkness, vanishing into the unseen, objective void that he engineered as his final, terrifying statement of visual truth.