Causae-Lex: The Jurist’s Final Verdict

The moment the heavy, bronze-studded door to Causae-Lex was pushed open, the air rushed out—cold, dense, and heavy with the pervasive, unsettling odor of old vellum, dried ink, and the sharp scent of mineral paper preservative. The name, combining the concept of a cause or case with law or rule, perfectly captured the manor’s function: a physical space dedicated to finding the perfect legal argument, now embodying its own absolute ethical vacuum. This abandoned Victorian house was structured not for domestic comfort, but for unwavering, logical precision, its internal layout a bewildering maze of small, well-lit study cells and soundproofed chambers designed to maximize focus on arcane legal texts.

The final inhabitant was Judge Cornelius Quibell (retired, though he never stopped studying), a brilliant, but intensely reclusive master jurist and legal philosopher of the late 19th century. Judge Quibell’s profession was the application of law and the meticulous balancing of evidence and statute. His singular obsession, however, was the creation of the ‘Final Edict’—a single, perfect, flawless legal ruling that would, through the absolute synthesis of all previous law, deliver the ultimate, objective truth of justice, free of all human bias or interpretive error. After a single, deeply regretted mistrial, he retreated to the manor. He dedicated his final years to resolving this single, terrifying goal, believing that the only way to achieve perfect justice was to understand the ultimate absence of all ambiguity. His personality was intensely rigorous, fearful of human fallibility, and utterly consumed by the pursuit of judicial finality.

The Docket Chamber

Judge Quibell’s mania culminated in the Docket Chamber. This secure, light-tight room was where he stored every legal argument and citation he had ever considered and then deemed flawed or contradictory. His journals, written in an elegant, fading script that eventually dissolved into complex, contradictory flowcharts of legal clauses, were found sealed inside a hollow volume of Roman law. He stopped trying to cite precedents and began trying to synthesize the Final Edict, concluding that the only way to achieve absolute, unbiased justice was to eliminate the need for an advocate or jury. “The law is a lie; the verdict is a choice,” one entry read. “The final justice requires the complete surrender of all interpretation. The truth must be a single, self-evident, unstated conclusion.”

The house preserves his ethical anxiety structurally. Many internal door handles are custom-made, with one side polished brass and the other side rough, cold iron, forcing a physical reminder of the opposing natures of mercy and strictness upon anyone entering a room.

The Final Seal in the Abandoned Victorian House

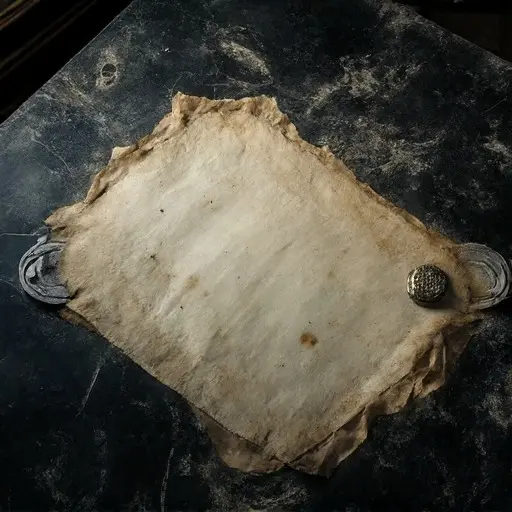

Judge Cornelius Quibell was last heard working in his library, followed by a sudden, intense sound of heavy paper being violently flattened and then immediate, profound silence. He did not leave the manor. The next morning, the library was cold, the papers scattered, and the man was gone. No body was found, and the only evidence was the singular, physical state of his final parchment.

The ultimate chilling clue is the blank parchment. It is the final page of his work—the Final Edict achieved, containing no words, no signatures, and no human judgment. The seal stamp is smooth, designed to authenticate nothingness. This abandoned Victorian house, with its towering silent libraries and symbolic door handles, stands as a cold, imposing testament to the master jurist who pursued the ultimate, unbiased truth of law, and who, in the end, may have successfully composed the ruling that demanded absolute silence, vanishing into the unwritten, objective justice that he engineered as his final, terrifying statement of law.