The Silent Glare of Lumina-Forge Hall

Lumina-Forge Hall was a strikingly unique mansion built of pale, smooth stone, characterized by its numerous windows of varying sizes and a massive, disproportionate central dome crowning its highest turret. The name suggested a place where light was created and controlled. The house sat on the highest, most exposed ridge in the area, offering an unparalleled view of the night sky, yet making it perpetually vulnerable to the elements. Upon entering, the air was immediately cold, thin, and carried a potent, almost chemical scent of oxidized copper, ozone, and old glass cleaner. The floors were polished wood, now dull and slick with dust, amplifying every faint sound into a disconcerting echo. The silence here was absolute, an unnatural stillness that felt like the atmosphere had been perfectly evacuated. This abandoned Victorian house was an instrument built for observation, now blindingly frozen.

The Astronomer’s Perfect Light

Lumina-Forge Hall was the fortified residence and astronomical laboratory of Dr. Alistair Finch, a brilliant but deeply obsessed amateur astronomer and optical engineer of the late 19th century. His professional life demanded relentless scrutiny of the cosmos, the meticulous calibration of lenses, and the pursuit of photometric perfection—measuring the exact brightness of distant stars. Personally, Dr. Finch was tormented by a crippling fear of cosmic insignificance and the ultimate unknowability of the universe. He built the Hall as his personal observatory, convinced that if he could just capture and measure the light of the oldest star, he would finally understand his place in the universe.

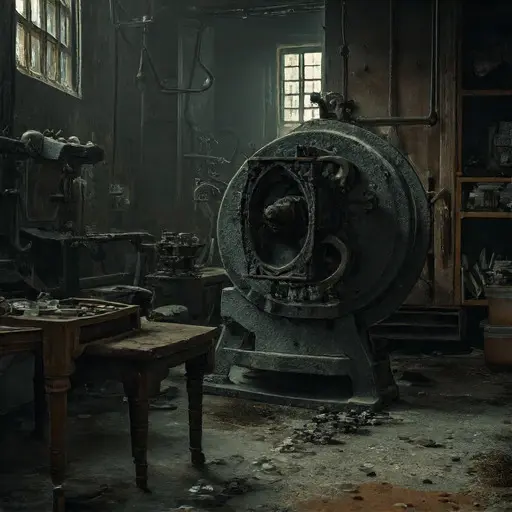

The Lens Grinding Chamber

Dr. Finch’s Lens Grinding Chamber, a damp-free, vibration-isolated room, was where he created his tools. We found his comprehensive Optical Ledger, bound in stiff linen, resting near the grinding wheel. His entries detailed the agonizing, months-long process of grinding and polishing his final, massive telescope lens, striving for an impossible degree of clarity. His notes revealed that he had begun naming his grinding failures after personal emotional shortcomings: “The Imperfection of Doubt,” “The Blurr of Regret.” His final project, detailed meticulously, was the lens itself, designed to be the largest, clearest lens ever made, capable of capturing the faintest, oldest light. His belief was that this light held the absolute, first truth.

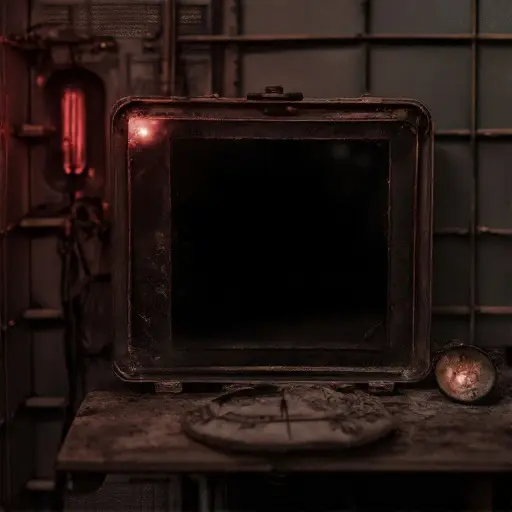

The Final Exposure Chamber

The most chilling space was a small, lead-lined room built into the base of the telescope turret, designed as a controlled environment for photographic plates. The room was dark, sterile, and cold. Here, we found his personal diary, tucked inside a metal developer tank. It revealed the tragic climax: when he finally aimed his perfect telescope at the night sky, he discovered that the faint, ancient light was so diluted by distance that his photographic plate registered nothing but absolute, unyielding blackness. His final, most poignant discovery was not a star, but the lack of one. On the chamber’s wall, he had scratched one final message next to the black exposure plate: “The light is real. The sight is nothing. The end is black.” His body was never found. The silent glare of Lumina-Forge Hall is the cold, empty light streaming into the unused telescope, a profound testament to an astronomer who sought absolute truth in the stars, only to find the chilling, dark emptiness of his own existence preserved within the highly engineered silence of his abandoned Victorian house.