Eerie Ledger Stops at the Silent Hearth of Oakhaven Grange

The Scullery and the Groundskeeper’s Records

Oakhaven Grange was a large, agricultural property, and our focus centered on Mr. Thomas Redding, the manor groundskeeper, who was in service from 1875 until 1901. Redding lived in the attached service cottage and was responsible for all external maintenance, animal care, and ledger-keeping related to the estate’s considerable operating costs. His life was defined by the cyclical nature of the seasons and the physical demands of agrarian upkeep. His fate remains unrecorded after a local fire destroyed the parish records for that year, leaving his disappearance after 1901 unexplained.

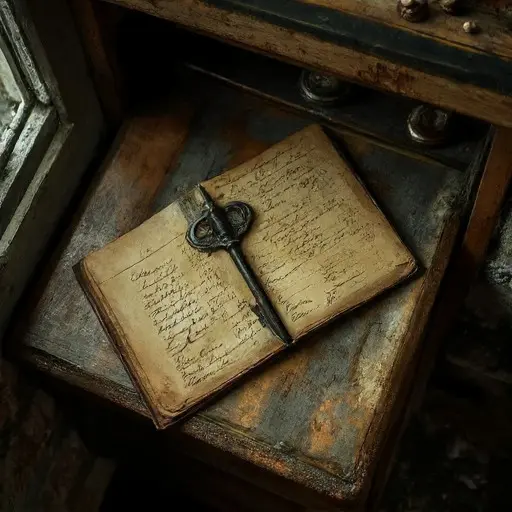

His records, however, survived. In a small, stone-walled scullery, used as his office, we located a tall, slender pine cabinet. Inside, protected from the worst of the damp, was his professional life: a series of small, hard-backed notebooks labeled Estate Expenditures and Stock Register.

The final book, bound in brown paper, was a meticulous record of seed purchases, livestock rotation, and wages paid to seasonal staff. The entries stopped abruptly on October 10, 1901, with a record for the purchase of a new scythe blade, its material cost itemized to the half-penny.

The Dry Goods and the Final Wages Envelope

The groundskeeper’s cottage, attached to the kitchen wing, was almost entirely bare. However, in a storage closet used for dry goods and equipment, we located one final, deeply personal clue to his departure. Behind a stack of unused burlap sacks and a coil of stiff, unused rope, was a small, tightly sealed wooden box, its lock broken, suggesting it was opened by someone who was not the owner.

Inside the box, there were no documents or letters, only two items: a clean, leather work glove, stiffened with age and dirt, and a single, heavy, blank white envelope, sealed with a plain, dark wax. The envelope bore no address, only a single word written in Redding’s strong, angular script: “Wages.”

When carefully opened, the envelope contained exactly one month’s salary in mixed coinage and banknotes, neatly stacked and tied with a piece of cotton thread. Redding had performed his final duty—purchasing the scythe blade—and meticulously calculated and withdrawn his final month’s pay. He had not spent the money, nor had he left a note of grievance. He simply sealed his earnings in a blank envelope and hid them, leaving the Grange with nothing but his final, precise ledger entries.

The house’s decay is overshadowed by the mystery of this lost act of closure. He left his final, essential tool record and his final, earned money, suggesting neither debt nor sudden death, but a silent, irreversible choice made on October 10, 1901, the manor groundskeeper having finally discharged himself of all duties and all material holdings associated with his life of service.